The Beautiful Mountain

"Viji, are you awake", asked Chetan.

I opened my eyes, and looked up into the cloudless, brilliant sky. A sky unlike anything visible from habitation. The city lights are bright and intoxicating, but the greatest beauty of the world may yet belong to its subtleties.

Chetan and I, the "before" photo. This was after Madhura's sharp comment to tuck my tummy. In my defense, the camera adds 5 pounds and so does the backpack!

There, all tucked away! Trailhead. 6600 feet.

On the hike up to the high camp, I had let out a silent prayer to the weather Gods, asking for a clear sky on my summit day. The rain Gods were smiling on me. But the wind Gods were not. A chill wind was blowing across the face of the mountain, freezing everything in its path. For the millionth time that night, I wished I had carried a heavier tent, rather than the light weight bivy sack. Even with three layers of clothing on me, all I could manage was a couple of hours of fitful sleep, drifting in and out of a tired twilight. For a moment, I wanted to just crawl up and ignore Chetan's voice. However there was a heat glowing in me that was brighter than the cold. I was burning up with summit fever.

"Yeah, dude", I answered.

"You want to just leave now?", he asked. Sleep is over rated, I tell myself. I am ready.

"Yeah, lets go", I said, and started fumbling around for my headlamp. It was 3:05 AM, 6th Aug 2006.

What are the indignities one will endure to reach a summit? I wore the same shirt for three days under my fleece. When I got back, the inner clothing was a regular salt factory, literally dripping with sweat. I had not washed my face or brushed my teeth, not because a toothbrush is heavy but because any water we wanted had to be laboriously melted from snow using precious fuel. Everything I carried, including my face was covered in dust and volcanic ash from the mountain. The ranger who hiked up to our high camp (1) suggested helpfully that he had extra "pack out bags", which meant that if you want to crap, you better crap in a bag and take your "stuff" back with you.

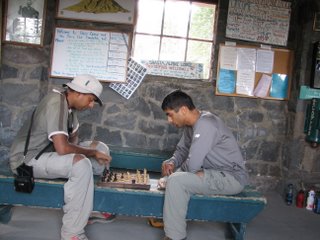

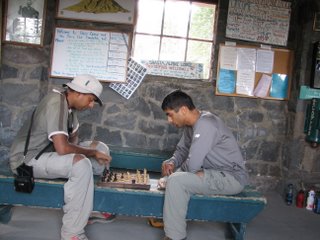

Chilling out at Horse Camp. 7900 feet.

However you may describe hiking and mountaineering, sexy is not a word that is ever going to fit. There are very many things that dictate against climbing higher. Against this array of irrefutable reasons, there stands a single emotion that drives men and women up and ahead. It is called summit fever. It is a positive energy that can drive one to achieve heights that are otherwise unthinkable. It also has a dark side, driving us to reach out beyond our abilities and get trapped high on the mountain, at the mercy of the weather it creates for itself (2). Eighty percent of all mountaineering fatalities happen during descent (3). I did not want to become the statistic. However, I did not yet know if I would play by the rules if push came to a shove. I had struggled too hard for this chance. To walk away from it would be a test of character tougher than any I have faced before. I simply hoped not to have to make that decision. The clear sky boded well. The high wind did not.

Madhura and I, on the way to Helen Lake. She is wearing the heavy high end mountaineering boots. The model she and Chetan are wearing are like a Hummer and can be used on Everest if they get there! I preferred a light weight Ferrari. Italian hand made moutaineering shoes that are just about good for Summer.

It all started two months back. We had climbed half dome in Yosemite National Park with a group of friends. This was a hill that had defeated me two years ago. I was back to finish what I had started. This time, I was two years away from my last cigarette, and twenty pounds away from my peak bulk. The signs were good, and I reached the top in comfortable, though unspectacular time. However, I did have that vital spare energy at the top of the dome. I bypassed the traffic jam at the cables towards the end, and traversed rapidly on the outside of the two cables, imitating what the stronger hikers, including Chetan, were doing in front of me. He noticed and came up to me. "You are ready for Shasta", he said. "The next time I go, you should make time to come with us". Of course, this was the same Chetan who walked with me on my previous, unsuccessful trip to half dome and mentioned calmly that "it was all psychological", when I felt like my lungs were about to explode. He thought I was ready. I was very far from sure. At that point, Half Dome was the most strenuous hike I had done. It started at 4000 feet and tops out at 8800 feet. Shasta on the other hand, runs from 6600 feet to 14000 feet. A big chunk of the climbing being above the 11000 feet ceiling where thin air and altitude related sickness and fatigue become a big factor. Forget about them being in the same league, they were not even the same game.

The infamous cables at half dome. It looks scarier than it actually is. When there are lot of people on them, there is a traffic jam. Some of the climbers bypass the jam by moving on the outside of the cables. It is faster, but riskier.

A week after the successful climb of half dome, we were at Mt. Whitney, the tallest peak in the contiguous 48 states of the US. This is one of the most popular amateur hikes in the US. There are two very good trails leading up to the summit. In late summer time, all it takes is fitness and will. No mountaineering involved. The plan was to get to the high camp at 12,000 feet on the first day. We struggled our way to the Outpost camp at 10,600 feet. Chetan was the sweeper (5) and probably had a good idea of how the slower hikers were doing. He suggested that we should just crash at the Outpost camp. However, doing so would have seriously jeopardized out summit attempt. Madhura and I talked everyone out of this idea and convinced them that we would all be able to reach the high camp. "There is plenty of time. Just take it slow.". A few of us started ahead with the idea of getting to the trail camp quickly and setting up the tents for the others. The trail from the Outpost to the High camp however turned out to be a brutal affair. To make matters worse, Chetan was reporting to us on the radio that many of those behind us were starting to get altitude sickness as we crossed 11,000 feet. Finally, Chetan called from midway between the two camps and informed us that there was no way anyone could go any further. He was camping where he stood. Those of us who were higher on the mountain started debating if we should go down or up. Going down would make summitting the next day difficult. Going up would need supplies which we did not have much of. While the debate was going on, Madhura seemed to make up her mind and started walking down resolutely. Everyone followed shortly after.

In 1996, an Indian expedition belonging to the Indo-Tibetian Border Police climbed Everest from the Tibetian side. They were caught high on the slopes of the mountain when a full fledged storm hit. The three man summit team had lost one of its members and two others were close to death when a pair of Japanese climbers reached them on their way to the summit. The climbers passed the injured Indians without a word and headed for the summit. No help, words, food or oxygen was exchanged. "We were too tired to help.", one of the climbers explained later. "Above 8000 meters is not a place where people can afford morality." This episode is fairly typical of mountaineering where "there is nothing I can do" is a common explanation for climbing over the dead and dying to reach the summit. Ethicists argue that this explanation is valid only if the choice is between saving someone and leaving them to die alone. They point out that there is a third alternative, one of compassion, where the climber stays with the dying person and comforts them till they pass away. Doing this of course, puts the summit attempt in an inconvenient jeopardy.

Walking back down to where Chetan and others had camped, one question kept plaguing me. Why had I kept pushing myself and others, when it was clear that we all needed a break? When we got back to where Chetan had camped, a plan was hatched to start at 3:00 in the morning instead of 5:00 to try for the summit. I made my decision and told Madhura that I will not be waking up. The summit should be less important than certain other things. I had imagined that making this decision on my first big climb would make it easier on the climbs to follow. That was not the case. On Shasta, the fever hit again with full fury, now bolstered by the failure at Whitney.

Helen Lake on Shasta stands at 10,400 feet and is not a lake at all. I did not see any lake. Just a sea of sloping, rising snow. It was going to be just Chetan and me climbing to the summit. Madhura had decided to stay back at the high camp, nursing her old skiing injury. She has climbed this one more than once before. The Ranger had mentioned that the average climb from Helen Lake took 6 hours. He suggested we should turn back no later than 1:00. Knowing I was the weak link, I estimated it was going to take me 8 hours. If we leave at 4:00, then I would reach the summit at 12:00, with 1 hour buffer before the turn around time, I reasoned. As it happened, we were up by 3:00. I started fumbling around the camp, getting my gear on.

The Helen Lake camp ground. The 'lake' is behind us. Red Banks is the most distant feature visible at the end of the slope.

After having done a certain amount of hiking, one begins to wonder what's next. The Avalanche Gulch route of Shasta presents a nice stepping stone from hiking to moutaineering. It is not so technical as to be inaccessible or dangerous to rookies. On the other hand, its height and massive icy slopes present a formidable challenge. The main difference from a normal hike was the equipment. We had to cart a small wagon load to our high camp before making the assault on the summit. Most hikes require little more than water and tennis shoes. Even ankle high hiking boots seem like a market driven overkill after a while. George Mallory (of "because it is there" fame), considered crampons and bottled oxygen to be cheating when he made the first assault on Everest. By his fifth expedition to his obsession, he had started considering both of these to be essential if there was to be any chance at all for climbing Everest. It took a couple of decades for the first ascent of Everest, even with these devices. It took a few more decades from there on to make the first ascent without oxygen. I don't think anyone is ever going to climb that mountain without crampons. It is just not possible. But then, that's what they said about oxygen too. When the first climb of Everest happened without oxygen, Tensing Norgay and several other eminent Sherpas sent out a note to the Nepali government demanding an investigation claiming that Messner and Habeler had cheated. A distraught Messner then went over to the Chinese side of Everest and climbed it again without oxygen and this time without even Sherpa support to prove his point. Now, no professional mountaineer would be taken seriously if he does not climb without oxygen.

Moutaineering Boots, check. Crampons, check (6). Ice Axe, check (7). Gaitors, check. Helmet, check. Headlamp, check. Backpack, check. Hiking pole, Hmmm.... My fifty dollar hiking pole was designed by someone who had obviously not been on a mountain. It needed my fingers to press on very fine buttons in order to collapse it. Problem was, each time I got my hands out of my gloves, they froze and became useless. With my gloves on, i was too clumsy to press anything fine. I finally gave up and informed Chetan that I was going to brave the slope without an pole. I was going to climb, no matter what. And I wanted to leave right away. The clock was ticking. Chetan suggested that was not a good idea, and gave me one of his poles. The 20 dollar WalMart pole could be adjusted without taking gloves off. It worked wonderfully. That's the way the cookie crumbles. Finally we were ready. I looked up with certain trepidation at the head lights of those who started before us, already high on the slope. "How in the hell am I going to climb this thing?", I thought. The previous night, I had ventured out of my tent to take a leak. A small dugout in the snow that acted as the camp toilet was no more than 10 yards from my tent. I fell about four times reaching it. When I finally got there, I could not unzip my fly with my gloves on. When I did take my gloves off and unzipped, my hands froze and so did my manhood. I could barely squeeze anything off. I could only laugh at my predicament, as I slunk off back to my tent, falling two more times along the way and crawled into my sleeping bag to start pretending I did not need to pee.

With the nightly escapade still fresh in my mind, I kept asking Chetan how to self arrest on the slope if I started sliding. "Hammer the claw of your ice axe into the snow, and then put your weight on it.", he said. I kept persisting with more questioning, until he finally said there was only one important safety tip I needed to know. "Don't fall", he said, and walked out into the cold, thin air.

Crunch. Crunch. The crampon bit into the hard snow, which had luckily frozen in the cold night. Lose slushy snow makes climbing difficult. Chetan struck a winding path, zig zagging on the slope so as to make the angle manageable. We hardly exchanged a word, I was concentrating on every step, making absolutely sure I don't fall. When in doubt, I kicked in deep steps before putting weight on my feet. Even with the measured pace and zig zag route that Chetan was setting, I had to repeatedly yell "Rest!" to make him stop. The rest was no rest at all. We could not very well sit and stretch on the wet glassy slope! The stops mostly consisted of driving the ice axe into the snow to secure myself and leaning on the hiking pole to catch my breadth. This was hard work. The wisdom of the helmet now dawned on me. The snow was several feet deep, and yet there were stones lying on top of them. The only way they could have gotten there is if they had fallen there sometime recently. The flip side of all this was that some of these stones were the size of Volkswagens. I tried not to think of my valiant helmet fighting against one of them goliaths!

On the way to Red Banks. The slope was already steep, however I had no idea what awaited me beyond Red Banks. Maybe if I had, I would not have sweated this part of the hike so much. From this point on, Chetan took most of the photos, since I did not think myself capable of carrying one ounce of weight more than I was carrying.

I could see the headlamps of those who had started ahead of us. And slowly, dawn started creeping up on us. Red Banks, so named for the large red sand and gravel, was visible at the end of the slope and was our immediate target. I put my head down and hiked with determination for a full hour. When I looked up, the end seemed even further than it had before! It was visible all the time, and it looked so near. I could almost imagine myself sprinting to it, get it over with. However, that was impossible. As we traveled higher and higher onto the slope, I gained in confidence. I figured that micro stepping straight up worked better for me than the wider steps on the zig zag route that Chetan preferred. I finally left his foot steps to strike my own path. And finally, inch by agonizing inch, we pushed closer to Red Banks (12800 feet).

Now there were about two dozen climbers scattered all over the slope, ahead and behind us. "Rocks!", came the shout from above. Everyone shouted "Rocks!", whether they saw it or not. The Ascent came to a complete stand still as those higher up anxiously looked down on those below, hoping nothing happened. "Is everyone OK?", came the next shout from above. This experience, which should have unnerved me, instead filled me with confidence. It was clear that safety was paramount here. The strongest climbers would go down first to help in an emergency. Nobody budged until everyone was sure everyone else was OK. Next stop Red Banks.

Chetan had started a small nose bleed, possibly because of the elevation or the icy wind blowing across the slope. However, it should be OK now, I thought, as we took the final steps into the bright red colored sand and gravel that marked the end of the snow face of Shasta. I did not expect what came next. While the large snow fields of the slope was finished, there was a narrow chute of compacted snow leading up and away, like a frozen stream with unclimbable loose graven on either of its banks. Impossibly, it was much, much steeper than the snow we had just traveled. In places we had to sink our ice axe into the snow and pull ourselves up, since it was too steep to rely on legs alone. To make matters worse, we were now in thin air. Fatigue hit me in full force. Till this point, I had managed to keep pace with Chetan, but now the difference in conditioning, strength and stamina started to tell. It was clear to me that Chetan was climbing conservatively. Conserving his strength and preserving it for the final push. Even then, he started to steadily outpace me. It was impossible to keep pace with him. I was finding it difficult even to keep him within sight. I don't know if it was hypoxia, or fatigue or a combination of both, but the inner voice in me started to show up around this time. The voice is that of a drill sergeant. "Take another ten steps, you weakling! Then you can slink and pant like a dog for all I care!", said the voice.

The chute on top of Red Banks, on the way to Misery Hill. Easily the toughest part of the climb for me. I was exhausted after every five or so steps. Chetan climbed very strongly through this entire section.

Reinhold Messner, the greatest mountaineer of our generation, and the first person to climb Everest without oxygen believes he has met Yetis on the hills. Others on K2 and Everest recount vivid memories of imaginary companions. Frank Smythe, writing about his 1933 attempt to climb Everest says the following. "This presence was strong and friendly. In his company, I could not feel lonely, neither could I come to any harm. It was always there to sustain me on my solitary climb up the snow covered slabs. Now as I halted and extracted some mint cake from my pocket, it was so near and so strong that instinctively I divided the cake into two halves and turned around with one half in my hand to offer it to my companion."

The hypoxia induced hallucinations of the truly high mountains are of course, stronger and vastly different from those of a relatively minor bump that we call Shasta. However, I had been curious to encounter my inner voice, to find out what it looked like and what it would say. It is rather jarring to confront him and find out that it is an asshole, and that he mostly says nasty things. I wish he had been someone a little nicer! Whatever it was, it cannot be denied that this separation of personality in the face of seemingly intractable obstacles is a good thing, and helps get one through difficult phases of the climb. Towards the end of the ice vein, my body was already adjusting to the altitude. I was learning to go a lot slower to conserve energy, and the body in turn was adapting to the thin air. By the time the last ice patch was behind us (8), I knew I was going to make it to the top.

The next step was Misery Hill, so called because most people think this is the summit, only to reach there and find out the true summit of Shasta behind it, and still some distance away. The crampons where off now, and after almost four hours of plodding through snow with crampons it was a relief to be on gravel and rocks again. I started plodding slowly towards the top, paying due deference to the altitude induced physical limitations. At around the same elevation, Mt. Whitney looks like a moonscape. A world of rock and ice of indescribable ugliness, looking like a scene straight out or Tolkien's Mordor. It is a world both forbidding and malevolent, screaming at you to back off and go home. Shasta however, is the beautiful mountain. Its year around snow cover presents an invitation that is intoxicating. At the top of Misery Hill, with the summit looking near enough, Chetan and I started having the first meaningful conversations of the entire climb. We talked about this and that, important and un-important stuff. I have no doubt that the bonds developed on the mountains will always be special and long lasting. In the simple adversity of a hill, the clutter and adornments that mask our true personalities are shed away and we stand in stark relief, exposing what we really are.

We had made good time and the sun had barely shown up by the time we got to the base of Misery Hill (in the background). However, using the break to apply sun screen right away so I don't have to fumble for the stuff later. One more aspect of Misery Hill that makes it miserable is that the summit of the hill is not what you see from this angle. There is more of the hill beyond eyesight. It seem to never end.

We resumed our climb after the conversation break and reached the top 5:45 hours after we started. The Ranger had said the average climb from Helen Lake was 4-6 hours. I cannot describe in word how happy I was to finally be among the elite league of "average" climbers! The reactions of the summiters was as varied as the faces of Shasta. Some people were retching their guts out because of altitude sickness. They reached the top with a raging headaches, driven forward by nothing more than the strength of their will (9). Others reached the top to crack open a beer can, proclaiming non-chalantly that Shasta "is overrated". I was merely relieved to have reached the top with some spare energy. I wanted a safe climb down and it looked like I had enough left in my cylinders to concentrate properly on the way down. Chetan emitted a snore. The first one was loud enough to startle the small group at the summit. He then proceeded into an even gear as he started a power nap.

Summit! 14162 feet. The final decision on whether one summits or not is with the mountain itself. I don't mean to sound spiritual, but I thank the mountain for letting me stand on her. Chetan fell asleep soon after this picture was taken. I started shivering badly.

"Mountains have taught me what I can truly achieve and Shasta has been the best teacher yet." That was the small piece of philosophy I left behind on the summit log book. After burning itself for hours to produce energy for the climb, the body could not take inactivity even for a short while. After just half hour or so on the summit, I was starting to shiver uncontrollably, even though the sun was shining brightly and I was well sheltered from the wind. We had to keep moving. Chetan woke up soon enough and we started descending. Comming down is always hard. There is no summit fever to push you along. While going up, you feel as if downhill would be a breeze. However, it never is. It just seems never ending. Shasta was no exception. However, there was one bright spot. The snow banks that took us 4 hours to climb were glissaded down in 4 minutes. Never having skiied of done anything that resembled the speed and rush of this experience made it especially memorable for me.

This photo was taken after we got back to Helen Lake after glissading down the snow bank in the background of the picture. It is a popular mis perception that reaching the summit of a big mountain releases this huge surge of energy and joy. It never works that way. Usually one is so tired that there is barely an acknowledgement of the achievement. The thought of walking all the way back still dominates. However, Glissading down the massive snow banks of Shasta is something that I am unlikely to forget anytime soon.

When we got down to Helen Lake, the honorary Sherpa of this trip, Madhura D, had already packed most of our stuff away. We finished up and left. As we were walking out of the trail, a couple out for a quite evening stroll at the trail head saw us with our heavy back packs and asked me how long we had "gone in". "Oh, two days," I said, "Today was our summit day." There was initially incomprehension, then a quick glance towards the peak that looked impossibly distant from where we stood and finally amazement. "You mean you went all the way to the top! And you were there today!". I was too tired to say anything beyond "Yes", but I was beaming with pride. After all, I was in the other set of shoes not long ago.

A couple of days after the climb, circumstances had forced me to sleep really late and wake up for a early morning meeting. As my alarm started beeping, visions of the cubicle farm and the day ahead clouded me and I wondered if I would doze off at the morning meeting. "Sleep is over rated", I then thought. "With this sleep, I can climb a mountain! I am ready. Bring it on!".

THE END.

(1) I have noticed that "high camp" is used in mountaineering literature to indicate the highest camp site before the actual summit. Truly tall peaks impose multiple camps at increasing elevations as a matter of necessity. However, on Shasta, the multiple camps exist only as a matter of convenience. The high camp can be reached after a good day's hike. The other camps are needed only if you start late.

(2) Big Mountains, including those the size of Shasta distort the geography of the region and create local weather patterns on themselves that are divorced from the larger weather condition of the area as a whole. There may be a thunderstorm on Shasta in the middle of the day while Shasta city at the base of the mountain endures a dry hot day.

(3) Source: Touching the Void.

(4) Contemporary mountaineering literature has fully embraced the idea that the successful climb must include a safe descent. Full accolades are paid to individuals who have the wisdom to turn back from within spitting distance of the summit, either because they were too late, or because they judged themselves too tired to risk it. A very good example of this is in Jon Krakauer's "Into Thin Air", where Goran Kropp, a Swedish man who bicycled all the way from Stockholm to Nepal before attempting the Everest summit comes across in brilliant light for his decision to turn back within 300 vertical feet of the summit, judging himself too weak to make the summit and climb back safely. On the other hand, Yasuko Namba, an amateur, clearly comes across in bad light for pushing herself far beyond her abilities. She is the first Japanese woman to have climbed Everest. However, she was one of the eight people killed in the disastrous descent that followed.

(5) The strongest hiker usually becomes the sweeper, walking behind the slowest hiker and making sure everyone was OK.

(6) Crampons are steel spikes that are worn under specialized mountaineering boots to gain traction on hard icy slopes.

(7) The Ice Axe is the single most essential mechanical gear used in snow and ice climbing. If you start sliding down a icy slope, the only way to stop yourself is by sinking the axe into the surface and putting all your weight on it. The Ice Axe was also necessary for glissading down the slopes while comming down. It controls speed.

(8) Shasta had snow in the middle portion in August 2006. There almost no snow below Helen Lake and above Misery Hill. I think the snow melts away from the top because Shasta is an active volcano and is still hot at the top (last eruption was about 200 years ago). This explanation of the absence of snow at the top is just my theory. I am not sure if this is accurate.

(9) Altitude sickness is a really funny thing and happens to different people at different altitudes. Some people start feeling it as early as 9000 feet. I have gone up 14000 feet without having encountered it yet. Only one thing is certain. It cannot be confused with strength, stamina or endurance. Strong climbers get it just as easily as not so strong ones.

Some Books of Interest:

- Jon Krakauer's Into Thin Air is a well researched book on the 1996 disaster on Everest.

- Maurice Herzog's Annapurna is supposed to be one of the greatest mountaineering books ever written. I have not been able to get my hands on a copy. Friends of mine who are reading this know what they need to do in order to assure themselves of my eternal love!

- Laurence Leamer's Ascent is a book with more of a philosophical incline. It is based on the life of the legendary american mountaineer Willi Unsoeld. Interestingly, Krakauer played with Unsoeld's kids when he was young.

- "Touching the Void" and "Everest IMAX, by David Breashears" are two unforgettable documentaries on mountaineering. Brashears filmed his movie in the same season that the events of Krakauer's book happened.

I opened my eyes, and looked up into the cloudless, brilliant sky. A sky unlike anything visible from habitation. The city lights are bright and intoxicating, but the greatest beauty of the world may yet belong to its subtleties.

On the hike up to the high camp, I had let out a silent prayer to the weather Gods, asking for a clear sky on my summit day. The rain Gods were smiling on me. But the wind Gods were not. A chill wind was blowing across the face of the mountain, freezing everything in its path. For the millionth time that night, I wished I had carried a heavier tent, rather than the light weight bivy sack. Even with three layers of clothing on me, all I could manage was a couple of hours of fitful sleep, drifting in and out of a tired twilight. For a moment, I wanted to just crawl up and ignore Chetan's voice. However there was a heat glowing in me that was brighter than the cold. I was burning up with summit fever.

"Yeah, dude", I answered.

"You want to just leave now?", he asked. Sleep is over rated, I tell myself. I am ready.

"Yeah, lets go", I said, and started fumbling around for my headlamp. It was 3:05 AM, 6th Aug 2006.

What are the indignities one will endure to reach a summit? I wore the same shirt for three days under my fleece. When I got back, the inner clothing was a regular salt factory, literally dripping with sweat. I had not washed my face or brushed my teeth, not because a toothbrush is heavy but because any water we wanted had to be laboriously melted from snow using precious fuel. Everything I carried, including my face was covered in dust and volcanic ash from the mountain. The ranger who hiked up to our high camp (1) suggested helpfully that he had extra "pack out bags", which meant that if you want to crap, you better crap in a bag and take your "stuff" back with you.

However you may describe hiking and mountaineering, sexy is not a word that is ever going to fit. There are very many things that dictate against climbing higher. Against this array of irrefutable reasons, there stands a single emotion that drives men and women up and ahead. It is called summit fever. It is a positive energy that can drive one to achieve heights that are otherwise unthinkable. It also has a dark side, driving us to reach out beyond our abilities and get trapped high on the mountain, at the mercy of the weather it creates for itself (2). Eighty percent of all mountaineering fatalities happen during descent (3). I did not want to become the statistic. However, I did not yet know if I would play by the rules if push came to a shove. I had struggled too hard for this chance. To walk away from it would be a test of character tougher than any I have faced before. I simply hoped not to have to make that decision. The clear sky boded well. The high wind did not.

It all started two months back. We had climbed half dome in Yosemite National Park with a group of friends. This was a hill that had defeated me two years ago. I was back to finish what I had started. This time, I was two years away from my last cigarette, and twenty pounds away from my peak bulk. The signs were good, and I reached the top in comfortable, though unspectacular time. However, I did have that vital spare energy at the top of the dome. I bypassed the traffic jam at the cables towards the end, and traversed rapidly on the outside of the two cables, imitating what the stronger hikers, including Chetan, were doing in front of me. He noticed and came up to me. "You are ready for Shasta", he said. "The next time I go, you should make time to come with us". Of course, this was the same Chetan who walked with me on my previous, unsuccessful trip to half dome and mentioned calmly that "it was all psychological", when I felt like my lungs were about to explode. He thought I was ready. I was very far from sure. At that point, Half Dome was the most strenuous hike I had done. It started at 4000 feet and tops out at 8800 feet. Shasta on the other hand, runs from 6600 feet to 14000 feet. A big chunk of the climbing being above the 11000 feet ceiling where thin air and altitude related sickness and fatigue become a big factor. Forget about them being in the same league, they were not even the same game.

A week after the successful climb of half dome, we were at Mt. Whitney, the tallest peak in the contiguous 48 states of the US. This is one of the most popular amateur hikes in the US. There are two very good trails leading up to the summit. In late summer time, all it takes is fitness and will. No mountaineering involved. The plan was to get to the high camp at 12,000 feet on the first day. We struggled our way to the Outpost camp at 10,600 feet. Chetan was the sweeper (5) and probably had a good idea of how the slower hikers were doing. He suggested that we should just crash at the Outpost camp. However, doing so would have seriously jeopardized out summit attempt. Madhura and I talked everyone out of this idea and convinced them that we would all be able to reach the high camp. "There is plenty of time. Just take it slow.". A few of us started ahead with the idea of getting to the trail camp quickly and setting up the tents for the others. The trail from the Outpost to the High camp however turned out to be a brutal affair. To make matters worse, Chetan was reporting to us on the radio that many of those behind us were starting to get altitude sickness as we crossed 11,000 feet. Finally, Chetan called from midway between the two camps and informed us that there was no way anyone could go any further. He was camping where he stood. Those of us who were higher on the mountain started debating if we should go down or up. Going down would make summitting the next day difficult. Going up would need supplies which we did not have much of. While the debate was going on, Madhura seemed to make up her mind and started walking down resolutely. Everyone followed shortly after.

In 1996, an Indian expedition belonging to the Indo-Tibetian Border Police climbed Everest from the Tibetian side. They were caught high on the slopes of the mountain when a full fledged storm hit. The three man summit team had lost one of its members and two others were close to death when a pair of Japanese climbers reached them on their way to the summit. The climbers passed the injured Indians without a word and headed for the summit. No help, words, food or oxygen was exchanged. "We were too tired to help.", one of the climbers explained later. "Above 8000 meters is not a place where people can afford morality." This episode is fairly typical of mountaineering where "there is nothing I can do" is a common explanation for climbing over the dead and dying to reach the summit. Ethicists argue that this explanation is valid only if the choice is between saving someone and leaving them to die alone. They point out that there is a third alternative, one of compassion, where the climber stays with the dying person and comforts them till they pass away. Doing this of course, puts the summit attempt in an inconvenient jeopardy.

Walking back down to where Chetan and others had camped, one question kept plaguing me. Why had I kept pushing myself and others, when it was clear that we all needed a break? When we got back to where Chetan had camped, a plan was hatched to start at 3:00 in the morning instead of 5:00 to try for the summit. I made my decision and told Madhura that I will not be waking up. The summit should be less important than certain other things. I had imagined that making this decision on my first big climb would make it easier on the climbs to follow. That was not the case. On Shasta, the fever hit again with full fury, now bolstered by the failure at Whitney.

Helen Lake on Shasta stands at 10,400 feet and is not a lake at all. I did not see any lake. Just a sea of sloping, rising snow. It was going to be just Chetan and me climbing to the summit. Madhura had decided to stay back at the high camp, nursing her old skiing injury. She has climbed this one more than once before. The Ranger had mentioned that the average climb from Helen Lake took 6 hours. He suggested we should turn back no later than 1:00. Knowing I was the weak link, I estimated it was going to take me 8 hours. If we leave at 4:00, then I would reach the summit at 12:00, with 1 hour buffer before the turn around time, I reasoned. As it happened, we were up by 3:00. I started fumbling around the camp, getting my gear on.

After having done a certain amount of hiking, one begins to wonder what's next. The Avalanche Gulch route of Shasta presents a nice stepping stone from hiking to moutaineering. It is not so technical as to be inaccessible or dangerous to rookies. On the other hand, its height and massive icy slopes present a formidable challenge. The main difference from a normal hike was the equipment. We had to cart a small wagon load to our high camp before making the assault on the summit. Most hikes require little more than water and tennis shoes. Even ankle high hiking boots seem like a market driven overkill after a while. George Mallory (of "because it is there" fame), considered crampons and bottled oxygen to be cheating when he made the first assault on Everest. By his fifth expedition to his obsession, he had started considering both of these to be essential if there was to be any chance at all for climbing Everest. It took a couple of decades for the first ascent of Everest, even with these devices. It took a few more decades from there on to make the first ascent without oxygen. I don't think anyone is ever going to climb that mountain without crampons. It is just not possible. But then, that's what they said about oxygen too. When the first climb of Everest happened without oxygen, Tensing Norgay and several other eminent Sherpas sent out a note to the Nepali government demanding an investigation claiming that Messner and Habeler had cheated. A distraught Messner then went over to the Chinese side of Everest and climbed it again without oxygen and this time without even Sherpa support to prove his point. Now, no professional mountaineer would be taken seriously if he does not climb without oxygen.

Moutaineering Boots, check. Crampons, check (6). Ice Axe, check (7). Gaitors, check. Helmet, check. Headlamp, check. Backpack, check. Hiking pole, Hmmm.... My fifty dollar hiking pole was designed by someone who had obviously not been on a mountain. It needed my fingers to press on very fine buttons in order to collapse it. Problem was, each time I got my hands out of my gloves, they froze and became useless. With my gloves on, i was too clumsy to press anything fine. I finally gave up and informed Chetan that I was going to brave the slope without an pole. I was going to climb, no matter what. And I wanted to leave right away. The clock was ticking. Chetan suggested that was not a good idea, and gave me one of his poles. The 20 dollar WalMart pole could be adjusted without taking gloves off. It worked wonderfully. That's the way the cookie crumbles. Finally we were ready. I looked up with certain trepidation at the head lights of those who started before us, already high on the slope. "How in the hell am I going to climb this thing?", I thought. The previous night, I had ventured out of my tent to take a leak. A small dugout in the snow that acted as the camp toilet was no more than 10 yards from my tent. I fell about four times reaching it. When I finally got there, I could not unzip my fly with my gloves on. When I did take my gloves off and unzipped, my hands froze and so did my manhood. I could barely squeeze anything off. I could only laugh at my predicament, as I slunk off back to my tent, falling two more times along the way and crawled into my sleeping bag to start pretending I did not need to pee.

With the nightly escapade still fresh in my mind, I kept asking Chetan how to self arrest on the slope if I started sliding. "Hammer the claw of your ice axe into the snow, and then put your weight on it.", he said. I kept persisting with more questioning, until he finally said there was only one important safety tip I needed to know. "Don't fall", he said, and walked out into the cold, thin air.

Crunch. Crunch. The crampon bit into the hard snow, which had luckily frozen in the cold night. Lose slushy snow makes climbing difficult. Chetan struck a winding path, zig zagging on the slope so as to make the angle manageable. We hardly exchanged a word, I was concentrating on every step, making absolutely sure I don't fall. When in doubt, I kicked in deep steps before putting weight on my feet. Even with the measured pace and zig zag route that Chetan was setting, I had to repeatedly yell "Rest!" to make him stop. The rest was no rest at all. We could not very well sit and stretch on the wet glassy slope! The stops mostly consisted of driving the ice axe into the snow to secure myself and leaning on the hiking pole to catch my breadth. This was hard work. The wisdom of the helmet now dawned on me. The snow was several feet deep, and yet there were stones lying on top of them. The only way they could have gotten there is if they had fallen there sometime recently. The flip side of all this was that some of these stones were the size of Volkswagens. I tried not to think of my valiant helmet fighting against one of them goliaths!

I could see the headlamps of those who had started ahead of us. And slowly, dawn started creeping up on us. Red Banks, so named for the large red sand and gravel, was visible at the end of the slope and was our immediate target. I put my head down and hiked with determination for a full hour. When I looked up, the end seemed even further than it had before! It was visible all the time, and it looked so near. I could almost imagine myself sprinting to it, get it over with. However, that was impossible. As we traveled higher and higher onto the slope, I gained in confidence. I figured that micro stepping straight up worked better for me than the wider steps on the zig zag route that Chetan preferred. I finally left his foot steps to strike my own path. And finally, inch by agonizing inch, we pushed closer to Red Banks (12800 feet).

Now there were about two dozen climbers scattered all over the slope, ahead and behind us. "Rocks!", came the shout from above. Everyone shouted "Rocks!", whether they saw it or not. The Ascent came to a complete stand still as those higher up anxiously looked down on those below, hoping nothing happened. "Is everyone OK?", came the next shout from above. This experience, which should have unnerved me, instead filled me with confidence. It was clear that safety was paramount here. The strongest climbers would go down first to help in an emergency. Nobody budged until everyone was sure everyone else was OK. Next stop Red Banks.

Chetan had started a small nose bleed, possibly because of the elevation or the icy wind blowing across the slope. However, it should be OK now, I thought, as we took the final steps into the bright red colored sand and gravel that marked the end of the snow face of Shasta. I did not expect what came next. While the large snow fields of the slope was finished, there was a narrow chute of compacted snow leading up and away, like a frozen stream with unclimbable loose graven on either of its banks. Impossibly, it was much, much steeper than the snow we had just traveled. In places we had to sink our ice axe into the snow and pull ourselves up, since it was too steep to rely on legs alone. To make matters worse, we were now in thin air. Fatigue hit me in full force. Till this point, I had managed to keep pace with Chetan, but now the difference in conditioning, strength and stamina started to tell. It was clear to me that Chetan was climbing conservatively. Conserving his strength and preserving it for the final push. Even then, he started to steadily outpace me. It was impossible to keep pace with him. I was finding it difficult even to keep him within sight. I don't know if it was hypoxia, or fatigue or a combination of both, but the inner voice in me started to show up around this time. The voice is that of a drill sergeant. "Take another ten steps, you weakling! Then you can slink and pant like a dog for all I care!", said the voice.

Reinhold Messner, the greatest mountaineer of our generation, and the first person to climb Everest without oxygen believes he has met Yetis on the hills. Others on K2 and Everest recount vivid memories of imaginary companions. Frank Smythe, writing about his 1933 attempt to climb Everest says the following. "This presence was strong and friendly. In his company, I could not feel lonely, neither could I come to any harm. It was always there to sustain me on my solitary climb up the snow covered slabs. Now as I halted and extracted some mint cake from my pocket, it was so near and so strong that instinctively I divided the cake into two halves and turned around with one half in my hand to offer it to my companion."

The hypoxia induced hallucinations of the truly high mountains are of course, stronger and vastly different from those of a relatively minor bump that we call Shasta. However, I had been curious to encounter my inner voice, to find out what it looked like and what it would say. It is rather jarring to confront him and find out that it is an asshole, and that he mostly says nasty things. I wish he had been someone a little nicer! Whatever it was, it cannot be denied that this separation of personality in the face of seemingly intractable obstacles is a good thing, and helps get one through difficult phases of the climb. Towards the end of the ice vein, my body was already adjusting to the altitude. I was learning to go a lot slower to conserve energy, and the body in turn was adapting to the thin air. By the time the last ice patch was behind us (8), I knew I was going to make it to the top.

The next step was Misery Hill, so called because most people think this is the summit, only to reach there and find out the true summit of Shasta behind it, and still some distance away. The crampons where off now, and after almost four hours of plodding through snow with crampons it was a relief to be on gravel and rocks again. I started plodding slowly towards the top, paying due deference to the altitude induced physical limitations. At around the same elevation, Mt. Whitney looks like a moonscape. A world of rock and ice of indescribable ugliness, looking like a scene straight out or Tolkien's Mordor. It is a world both forbidding and malevolent, screaming at you to back off and go home. Shasta however, is the beautiful mountain. Its year around snow cover presents an invitation that is intoxicating. At the top of Misery Hill, with the summit looking near enough, Chetan and I started having the first meaningful conversations of the entire climb. We talked about this and that, important and un-important stuff. I have no doubt that the bonds developed on the mountains will always be special and long lasting. In the simple adversity of a hill, the clutter and adornments that mask our true personalities are shed away and we stand in stark relief, exposing what we really are.

We resumed our climb after the conversation break and reached the top 5:45 hours after we started. The Ranger had said the average climb from Helen Lake was 4-6 hours. I cannot describe in word how happy I was to finally be among the elite league of "average" climbers! The reactions of the summiters was as varied as the faces of Shasta. Some people were retching their guts out because of altitude sickness. They reached the top with a raging headaches, driven forward by nothing more than the strength of their will (9). Others reached the top to crack open a beer can, proclaiming non-chalantly that Shasta "is overrated". I was merely relieved to have reached the top with some spare energy. I wanted a safe climb down and it looked like I had enough left in my cylinders to concentrate properly on the way down. Chetan emitted a snore. The first one was loud enough to startle the small group at the summit. He then proceeded into an even gear as he started a power nap.

"Mountains have taught me what I can truly achieve and Shasta has been the best teacher yet." That was the small piece of philosophy I left behind on the summit log book. After burning itself for hours to produce energy for the climb, the body could not take inactivity even for a short while. After just half hour or so on the summit, I was starting to shiver uncontrollably, even though the sun was shining brightly and I was well sheltered from the wind. We had to keep moving. Chetan woke up soon enough and we started descending. Comming down is always hard. There is no summit fever to push you along. While going up, you feel as if downhill would be a breeze. However, it never is. It just seems never ending. Shasta was no exception. However, there was one bright spot. The snow banks that took us 4 hours to climb were glissaded down in 4 minutes. Never having skiied of done anything that resembled the speed and rush of this experience made it especially memorable for me.

When we got down to Helen Lake, the honorary Sherpa of this trip, Madhura D, had already packed most of our stuff away. We finished up and left. As we were walking out of the trail, a couple out for a quite evening stroll at the trail head saw us with our heavy back packs and asked me how long we had "gone in". "Oh, two days," I said, "Today was our summit day." There was initially incomprehension, then a quick glance towards the peak that looked impossibly distant from where we stood and finally amazement. "You mean you went all the way to the top! And you were there today!". I was too tired to say anything beyond "Yes", but I was beaming with pride. After all, I was in the other set of shoes not long ago.

A couple of days after the climb, circumstances had forced me to sleep really late and wake up for a early morning meeting. As my alarm started beeping, visions of the cubicle farm and the day ahead clouded me and I wondered if I would doze off at the morning meeting. "Sleep is over rated", I then thought. "With this sleep, I can climb a mountain! I am ready. Bring it on!".

THE END.

(1) I have noticed that "high camp" is used in mountaineering literature to indicate the highest camp site before the actual summit. Truly tall peaks impose multiple camps at increasing elevations as a matter of necessity. However, on Shasta, the multiple camps exist only as a matter of convenience. The high camp can be reached after a good day's hike. The other camps are needed only if you start late.

(2) Big Mountains, including those the size of Shasta distort the geography of the region and create local weather patterns on themselves that are divorced from the larger weather condition of the area as a whole. There may be a thunderstorm on Shasta in the middle of the day while Shasta city at the base of the mountain endures a dry hot day.

(3) Source: Touching the Void.

(4) Contemporary mountaineering literature has fully embraced the idea that the successful climb must include a safe descent. Full accolades are paid to individuals who have the wisdom to turn back from within spitting distance of the summit, either because they were too late, or because they judged themselves too tired to risk it. A very good example of this is in Jon Krakauer's "Into Thin Air", where Goran Kropp, a Swedish man who bicycled all the way from Stockholm to Nepal before attempting the Everest summit comes across in brilliant light for his decision to turn back within 300 vertical feet of the summit, judging himself too weak to make the summit and climb back safely. On the other hand, Yasuko Namba, an amateur, clearly comes across in bad light for pushing herself far beyond her abilities. She is the first Japanese woman to have climbed Everest. However, she was one of the eight people killed in the disastrous descent that followed.

(5) The strongest hiker usually becomes the sweeper, walking behind the slowest hiker and making sure everyone was OK.

(6) Crampons are steel spikes that are worn under specialized mountaineering boots to gain traction on hard icy slopes.

(7) The Ice Axe is the single most essential mechanical gear used in snow and ice climbing. If you start sliding down a icy slope, the only way to stop yourself is by sinking the axe into the surface and putting all your weight on it. The Ice Axe was also necessary for glissading down the slopes while comming down. It controls speed.

(8) Shasta had snow in the middle portion in August 2006. There almost no snow below Helen Lake and above Misery Hill. I think the snow melts away from the top because Shasta is an active volcano and is still hot at the top (last eruption was about 200 years ago). This explanation of the absence of snow at the top is just my theory. I am not sure if this is accurate.

(9) Altitude sickness is a really funny thing and happens to different people at different altitudes. Some people start feeling it as early as 9000 feet. I have gone up 14000 feet without having encountered it yet. Only one thing is certain. It cannot be confused with strength, stamina or endurance. Strong climbers get it just as easily as not so strong ones.

Some Books of Interest:

- Jon Krakauer's Into Thin Air is a well researched book on the 1996 disaster on Everest.

- Maurice Herzog's Annapurna is supposed to be one of the greatest mountaineering books ever written. I have not been able to get my hands on a copy. Friends of mine who are reading this know what they need to do in order to assure themselves of my eternal love!

- Laurence Leamer's Ascent is a book with more of a philosophical incline. It is based on the life of the legendary american mountaineer Willi Unsoeld. Interestingly, Krakauer played with Unsoeld's kids when he was young.

- "Touching the Void" and "Everest IMAX, by David Breashears" are two unforgettable documentaries on mountaineering. Brashears filmed his movie in the same season that the events of Krakauer's book happened.

Comments